|

In 1869 the freehold was sold to the Hartleys of Sunderland, and Bowen becoming bankrupt just afterwards, the Hartleys sold the works in 1870 to Chance Bros. & Co.,*[ An Indenture dated May 19th, 1870, was made between James Hartley and John James Kayll of the first part, John Hartley, Thomas Blenkinsop Hartley, and Hartley Perks Kayll of the second part, and James Timmins Chance, Robert Lucas Chance, Edward Chance, John Homer Chance, and Henry Chance of the third part.] of Smethwick, near Birmingham (now a limited company), who carried it on till May, 1873, when it was finally closed.

The writer recently had the advantage of interviewing William Stonier (now deceased), of Waltom, Clevedon, who was apprenticed at Birmingham, and came to Nailsea when the glass-works were taken over by the Chances. With Stonier many men came from Birmingham, chiefly glass-blowers and “flatteners,” the unskilled labourers being Somerset men. It is stated that this firm employed from 200 to 250 hands at Nailsea — sometimes more — and some of the blowers of heavy glass earned from £6 to £8 a week.

Chance & Co. did not buy the Nailsea works as a good speculation, but to keep other workers out. They manufactured only sheet and rolled plate glass, of which they kept a large stock; some of it was sent by water to Ireland, Scotland, and Bristol Conflicting statements are made as to the reasons why Chance & Co. closed the Nailsea works. It has been stated in print that the quality of the coal obtained at that time was so poor that it did not give sufficient heat for glass-making. Others report that the machinery became worn out, and that some of it fell into adjacent holes. Others, again, say that some of the buildings collapsed, and the firm suffered considerably from the endless expenditure in keeping the works in repair. The glass is said, too, to have been of poor quality in the seventies. But the true reason is probably summed up in the words, “The works did not pay.”

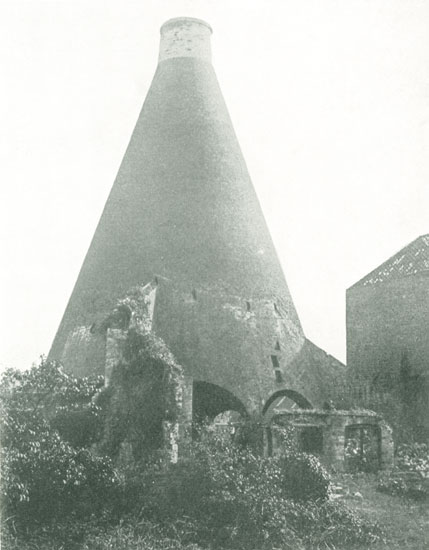

According to Stonier, Chance & Co.’s outlay on taking over the dilapidated works is said to have been between £30,000 and £40,000. After the works had been closed for several years, Samuel Davis, of the “Royal Oak Inn,” Nailsea, at the sale held on July 25th, 1889, *[Sale conducted by Alexander, Daniel, Selfe & Co., Corn Street, Bristol] bought the works and offices, †[It is stated that Davis only paid £1,200 for this property, and that afterwards he sold all the iron connected with the works for over £800.] with about 410 feet frontage to the main road from Nailsea to Bristol, on the condition that the glass-making ceased at the Nailsea works (although no objection was made to bottle-making). Some of the machinery went back to Birmingham. A double cottage on the north side of the works was, previously to 1907, a public-house known as the “Glass-Makers’ Arms.” A large building, formerly used for two French kilns, adjoining the “ Royal Oak Inn” and the old gas works and gas retort, has now been converted into the Nailsea rifle range. All the other buildings, including the annealing sheds, cones, furnaces, kilns, retorts, cutting-rooms, carpenters’ shops, ware-rooms, offices, stables, cart-sheds, and yards, are in a ruinous condition; but the ever-increasing growth of ivy and blackberry bushes now lends an almost picturesque aspect to the scene. Mr. S. Davis died on February 9th, 1905, and those portions of the works which he owned at the time of his death were again offered for sale by auction on June 15th, 1905.

The glass works were distinguished by “cones,” in the centre of which was the furnace resting on arches, where a relay of glass vessels was prepared for the furnace. Two of these “cones” are still standing; but the largest at the west end (No.i.) ‡[From a photograph by Mr. Tom Thatcher, June 8th, 1905.] was demolished by means of dynamite in 1905 for the purpose of obtaining bricks (few of which were afterwards sold).

|